Chris Barbey, Ph.D. is a researcher at the University of Florida studying strawberry flavor and disease resistance.

Brand new USDA regulations for crop biotechnology will begin phasing in during June 2020. The new “SECURE” rules (Sustainable, Ecological, Consistent, Uniform, Responsible, Efficient) govern what is — and isn’t — required for USDA review before going to market with a biotech crop. These rules could have immediate impacts on your research priorities, particularly if you already work in crop genetic improvement and/or plant transformation. They will also broadly reshape the future of crops developed using Genetic Engineering (GE). So, what are these new rules?

The USDA no longer requires review of:

- New GE crop varieties that are similar to previously approved GE crops.

- Single base pair substitutions or insertions/deletions (e.g. CRISPR gene editing).

- Gene insertions from compatible plant species (g. cis genetics).

- Foreign regulatory DNA (e.g. promoters, terminators, T-DNA).

- Plants engineered using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

The USDA still requires regulatory review of:

- New GE crops with novel mechanisms-of-action or gene combinations.

- New GE crops containing foreign genes.

- New GE crops containing Plant Incorporated Protectants (e.g. disease-resistance or pest-resistance genetics).

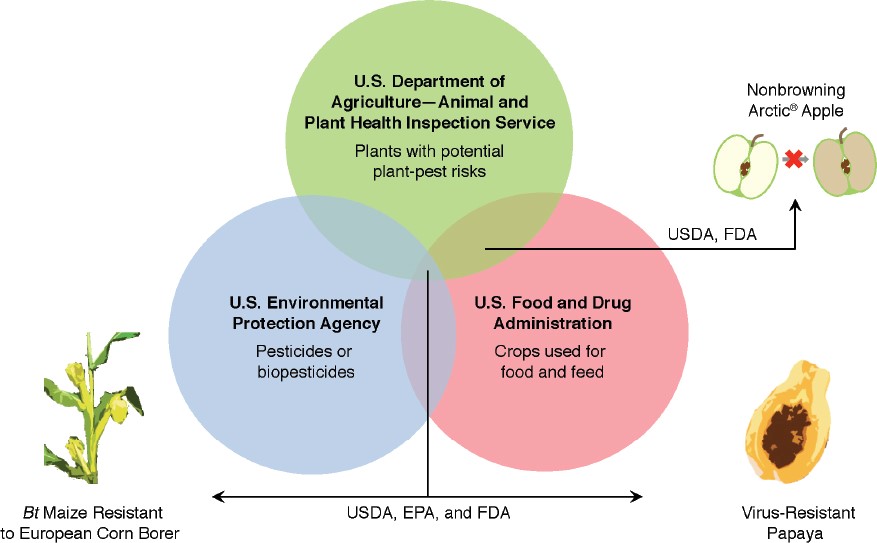

This doesn’t mean you can sell your CRISPR-edited microgreens next weekend at the farmers market, however. The USDA is only one-third of the “Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology” created by the U.S. Congress in 1986 (see figure). And besides U.S.-based agencies, over thirty world-wide governmental bodies regulate GE crops. Often it is financially necessary to obtain regulatory approval in many nations, regardless of the breadth of your intended market, because accidental shipments can represent enormous liability.

“The Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology (1986)” gives U.S. regulatory agencies shared responsibility in reviewing genetically engineered crops. The new SECURE rule (2020), issued by USDA-APHIS, updates what USDA considers necessary to review in their share of the Coordinated Framework.

However, these changes at USDA will be impactful and reverberate throughout the plant science community. On average, a new GE variety takes 13 years and $130 million of laboratory and field research before market. The regulatory process commonly spans 4 – 7 years or beyond, with around 75 different studies being conducted before achieving U.S. regulatory approval. The USDA estimates that these new rules may “…shave an estimated $3.6 million from the already hefty price tag of developing new genetically engineered crops.”

Developing GE varieties will still be difficult in terms of both science and their regulation, make no mistake. However, transferring already-approved genes into a new and diverse varieties — or into entirely new crops — should become much more feasible. These rules provide interesting opportunities for university plant breeders and small start-up companies to fill certain niches in GE crop creation.

As the first major update to the coordinated framework in thirty years, this policy change represents a considered reaction to three decades of research in GE safety and efficacy. These rules broadly follow recommendations from the 2016 National Academies of Science report on genetic engineering, which suggested streamlined review of non-novel GE traits and the reform of the “process-focused” regulatory system. These rules bring the USDA in-line with their original 1986 intention to regulate new varieties based on the “characteristics of the organism, the target environment, and the type of application” rather than the process used to create them. In practice, the previous USDA rules applied very narrowly to Agrobacterium-mediated GE crops. As noted in the National Academies of Science report, new technologies like gene editing exposed some of the logical contradictions of the existing regulatory approach, and the report recommended that agencies should focus instead on reviewing novel characteristics and hazards.

Reactions to these new rules from plant scientists, policy academics, and stakeholders has been positive.

ASPB Science Policy Committee chair Dr. Nathan Springer explains, “The new SECURE rules developed by the USDA provide a step towards rational regulation of gene editing and transgenic organisms. These policies provide new opportunities for basic science and crop improvement.”

The National Corn Growers Association and the American Seed Trade Association have both put out statements in support of the rules changes, citing the importance of supporting innovation in agriculture and streamlining the regulatory process. The National Law Review’s article on the new SECURE rules referenced the obvious and dire need for modernizing the previous regulations, while also noting the difficult-to-predict potential impact on consumer confidence.

Finally, your take-away:

It’s about to become a bit simpler to bring gene-edited and non-novel GE varieties to market. Field trialing of gene edited and GE organisms will also become less complicated. If you are an academic working in crop genetic improvement, you should consult with your university’s technology transfer office about these new rules.

Ask any questions you have about these new rules below, no matter how technical. We will invite policy experts to review and answer your questions. And we’ll compile those dialogs for a follow-up Q&A blog post, so please watch this space.

Sources:

National Academies of Sciences, E.a.M., 2016 Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

About the SECURE Rule, https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/biotechnology/biotech-rule-revision.

(a) this is fantastic news for American farmers.

(b) just wait until the hang-wringing and negative comments to come flooding in from people who don’t even understand the basics of evolution.

Meanwhile in Europe, organic farmers are happily growing mutagenic crops while transgenic and CRISPR varieties sit on the shelf gathering dust.

And in Africa and India people are starving for the same reasons… because people like Vanadan Shiva won’t stop spreading bad information and scaring politicians.

Does the USDA has any strategy for public engagement?

Although this regulatory framework will help in the democratization of GE, I wonder about public acceptance and confidence

Thank you