Guest blog post from Tim Jeffers at University of California, Berkeley

On a Saturday at the Berkeley Farmer’s Market, under a sign that says “Talk to a Scientist!”, you might get a chance to meet one of us, graduate students and young researchers of plant and microbial biology. We will have cool props and organisms you can learn about: algae that turn from green to red when grown in sugar, bacteria that smell like soil on a spring day, or a basket of broccoli, cabbage, kohlrabi, and other diverse crops from the same species – revealing the clever ways humans have manipulated plants for centuries. If you have a scientific question you’ve always wondered about, maybe you will fill out one of our “Ask a Scientist” cards (inspired by fellow scientists in Tennessee) so that we can research and email a thoughtful response to you.

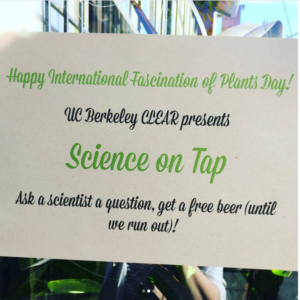

Or, if you attended the San Francisco March for Science or Earth Day at the Oakland Zoo, you may have found us providing you with ways to dress up in a lab coat and write signs about why you love science. You might even have gotten a free beer from us at an Oakland bar for one of our “Science on Tap” events, where we talked to you about how cool we think plants are on Fascination of Plants Day. All we want to do is talk to you about science—what it means to you, how it impacts society, even what makes you uncomfortable about it—and help you get to know who we are. We are just your neighbors with a passion for improving plants, food, and agriculture and unveiling life’s mysteries.

Why are we doing these types of community outreach events? We are members of the UC Global Food Initiative-funded student group CLEAR (Communication, Literacy, and Education in Agricultural Research) in UC Berkeley’s Department of Plant and Microbial Biology. In this year of political turmoil, we felt that the disregard for science as portrayed in politics and the media had reached a tipping point. We wanted to do our part to earn the public’s trust in science. CLEAR has always prioritized outreach, including organizing many events to educate ourselves and others on the policies, economics, ecology, and media landscape surrounding food and agriculture. These include The Millet Project, an effort to sensitize consumers to the benefits of cereal biodiversity, both in our diets and in our environment, and open conversations on the safety of GMOs at the Berkeley Public Library.

However, we wanted to add a more personal type of outreach to our agenda, in places where people might not expect to meet a scientist. So, we contacted bar owners and public event organizers and reserved places at these venues. It turned out to be much easier than we imagined and within days our calendars were filled with outreach activities.

Once we were at these events, it also turned out to be even easier to actually talk with people. The initial worries—will we sound too technical? Will people question our motives? Will they yell at us?—went away as curious people came to look at our props and flyers, converse with us, and, we think, left happy to have learned something new. We cover many subjects in these conversations, including antioxidants and cancer, the gut microbiome, the fate of the Chiquita banana, and, of course, how CRISPR works. More importantly, we get to hear the importance of science in our neighbor’s lives, whether it might be improving their lives, acting based on evidence, overcoming assumptions and biases, or just unveiling the wonders of the world. We quickly learned that it is so easy to discuss how cool and weird the natural world can be.

Of course, there are some not-so-great interactions. But, even these have been crucial to helping us develop our communication skills. Some people have walked up to us with opinions they obviously have no intention of changing. One or two people have even arguably pranked us with outlandish statements that make it difficult to respond. We’re learning how to redirect these conversations back to science or policy without making this person feel that their question was brushed aside.

Even so, there are difficult conversations that really pay off in shaping the ways people think about scientific issues. The most common question we get as plant scientists are about GMOs, their safety, and the companies who make them. In lecture-type events, dealing with staunchly anti-GMO believers can be difficult. Just recently in a public forum at the Berkeley City Library, two CLEAR members, Sonia and Virginia, shared that during their question and answer period their facts were challenged by a GMO skeptic, who announced that the presentation was biased and a waste of her time. They countered by explaining that they were there to try to find out what people’s concerns were and that, as students, they were trying to work to address them, but the skeptic probably left the event with a similar distrust of science.

In the more casual bar setting of “Science on Tap”, however, a similar situation turned out to be incredibly productive. When one CLEAR member, Becky, who studies plant-pathogen interactions, explained her research to a woman and her friend, the woman immediately became tense and antagonistic. However, after a 15-minute, civil discussion touching on genetic technologies, industrial agriculture, biodiversity, and GM crops in the developing world. Becky shared that she “validated her concerns, but also explained the best information that we have in the area. I don’t think this woman will be marching in support of GMOs any time soon, but I’m confident that the interaction exposed her to information she hadn’t received before from a friendly, engaged person.”

With these simple and casual conversations, we hope to get across to our neighbors that, even if they disagree with our viewpoints, scientists are just regular people like they are. We have fun! Like them, we are not always as productive as we’d like to be. And despite films’ portrayals of power-hungry, anti-social, and obsessive scientists, we might actually believe in work-life balance. More importantly, although we may study the details of a niche topic, the way we think about the world is not fundamentally different from the way anyone else does. We hope this encourages more people to talk with scientists.

More than just reaching out to people, we have found that we ourselves are reinvigorated by these conversations, and the impact of this experience carries over to our lab work. For instance, at the “Science on Tap” event I met a couple, who were starting to become passionate about science and agriculture through programs, like Radiolab and Nova, and their work in community gardens. They had very thoughtful questions and were captivated by certain facts I have taken for granted in my own education: that all plants derived from an unlikely union between a eukaryote and a photosynthetic bacterium; that a significant portion of human genes are shared between us and plants; and that human civilization depended on thousands of years discovering and manipulating plant processes to create the plants that give us our food.

Seeing the excitement of this couple took me back to when I was a freshman undergraduate. At that time I was not planning to be a scientist. Despite that, I still spent my free time watching nature documentaries in my school’s video library and reading about food security in National Geographic or Scientific American. I was enamored by biology because it revealed the complex mysteries of life, whether in cellular machinery or our interconnected global ecosystem. Even more, a career in science would allow me to start revealing these mysteries with the intent of improving our wellbeing through a more secure and equitable food system.

If anything, CLEAR’s ultimate goal is this: to get our neighbors to feel that sense of wonder about the natural world and to care about how good science and smart policy can improve all of our lives. Trust me, it is easy to do. If you are a scientist, find a farmer’s market, a festival, or a bar and engage with those around you about what science means to them and try to understand what their thoughts and concerns are and why. You will be doing your part to increase the appreciation of science in society, encourage your community to trust scientists, and you may even come back to the lab with a new appreciation of how your research fits into the innovation and wonder that science provides for everyone.

It is nice to think about bringing science home. I don’t know my neighbors well, but science (Botany) might provide a way to connect with them. I meet people at markets and don’t often mention my work.