2016 is the International Year of Pulses, which the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has been celebrating throughout the year by releasing infographics, information and hosting events; see these and more news here and at #IYP2016.

2016 is the International Year of Pulses, which the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has been celebrating throughout the year by releasing infographics, information and hosting events; see these and more news here and at #IYP2016.

Pulses are “the dehydrated edible seeds of leguminous plants that produce from one to twelve grains of various sizes, shapes and colours within a pod”. Pulses are lentils, broad beans, chickpeas, black beans, mung beans, pinto beans, kidney beans and more. Pulses are important for food security because, as they come from nitrogen-fixing plants, they are high in protein. By eating the plant products directly rather than after processing into meat or dairy products, the climate impact of your meal is lowered. Pulses are also good sources of micronutrients and fiber, something many people need to eat more of.

You may already eat pulses without being aware of it, as hummus, falafel, refried beans or tofu. Dried pulses are a bit more difficult to prepare, but because pulses are very inexpensive, pulse cookery is a good skill to acquire. The secret to preparing most pulses is to soak them overnight and cook them thoroughly, then rinse again after cooking; otherwise some people can find them upsetting to their digestive system. (Lentils are small enough that they can do without the overnight soaking, but bigger pulses usually benefit greatly from a long presoak to rehydrate the seed storage proteins and carbohydrates).

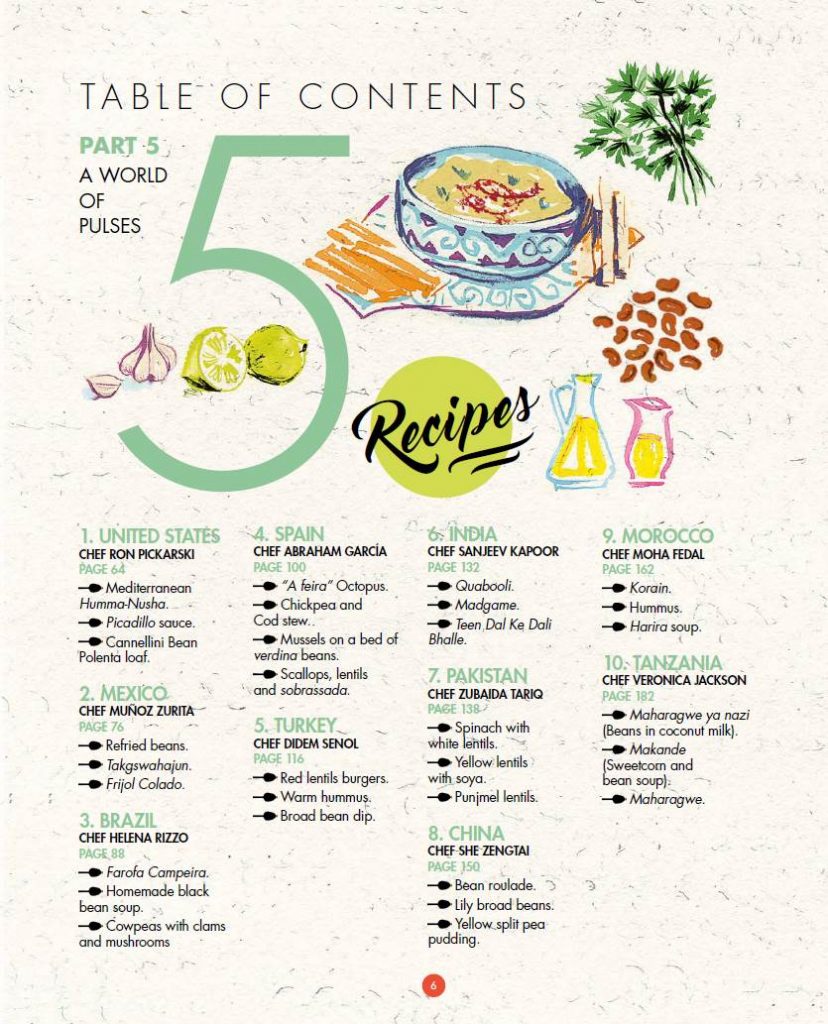

In honor of IYP2016, the FAO has released two versions of a free PDF book, Pulses: Nutritious seeds for a sustainable future, that cover pretty much everything you could ever want to know about pulses, from their taxonomy and nutritional information to how to prepare meals starting from the dried seeds. Here are links to the short 16 page version and the long 196 page version (available in Spanish, French, English, Arabic, Chinese and Russian). Both versions of the book are beautifully illustrated and include pulse-based recipes from chefs around the world.

For a busy scientist, cooking pulses from scratch may seem like a lot of work, but with a little planning (and judicious use of weekends), it can become a regular part of your routine. As scientists, we understand how nitrogen-fixing symbiosis benefits legumes. Why not take the next step and let those legumes benefit us, and the planet?